A buoyant lady extends her hand to me in a firm handshake, which means she is reliable, and starts talking as if she already knew me for a while. She does not speak Albanian very well, as she left the country with her mother in 1939, when she was five, and returning to her home-country became possible only in 1993.

World War II and Enver Hoxha’s communist regime of 40 years meant a whole lot of changes for Albania. She always wondered as to what had happened to the country during that time. Even though she missed Albania and Tirana only through her vague memories, her return had a deeper purpose: to carry on a legacy. In 1996 she opened in Tirana the Martin & Mirash Ivanaj Institute, a foundation to serve education and culture for Albanian pupils and students.

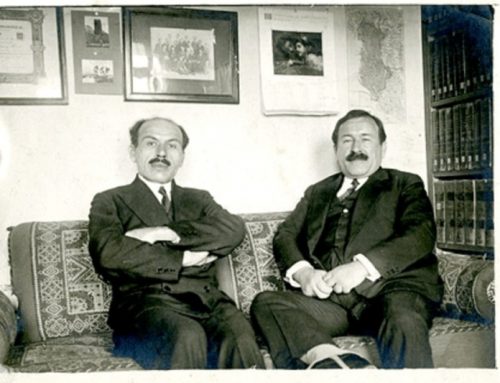

Drita Ivanaj is the only heir to these two Ivanaj brothers. Her father, Martin Ivanaj, was ultimately Chief of the Supreme Court of Albania. Starting off as a lawyer in Korca and then briefly in Shkodra, he established the first modern Civil and Penal Codes for the judicial system in Albania, rendered many judgments in a variety of fields, and started a collection of legal documents contained in over 20 manuscripts intended to be published after his retirement. Unfortunately, after the Italian invasion of Albania in 1939, followed by World War II, and the Albanian dictatorship, these precious documents were pilfered and disappeared together with the considerable collection of 16,600 books of the Ivanajs’ private library.

Drita’s uncle, Mirash Ivanaj, after graduating with two degrees from the University of Rome (‘La Sapienza’ of today), started his career as a teacher, who became also headmaster of the high school “28 Nentori” (November 28) in Shkodra. During the 1930s King Zog asked him to serve as Minister of Public Education. The King knew that the Ivanaj brothers, and especially Mirash, did not agree with his ruling, “but you [Mirash] are the only one I can trust to give a valid contribution to our country”. So Mirash opened the first public schools in Albania, known as the Ivanaj Reform of 1936. He later resigned from this position, as his reforms created a lot of opposition due to the educational standards he sought to apply throughout the Albanian educational system.

Large portraits of her family members adorn one of Drita’s office walls, where she has a large desk, a work table for holding meetings, and a setup of chairs and coffee table to share with visitors some relaxing moments. The corridor outside her office is filled with display cabinets, in which various items of her past are exhibited, such as some of her father’s and uncle’s documents, old photos, a family tree, objects and mementos inherited from her relatives on both maternal and paternal sides. The paternal family tree shows ancestors since 1444, during Skanderbeg’s era, while her maternal heritage, dating back to 1664, includes prelates, and distinguished society members, such as Lady Collins, her maternal grandmother’s aunt, who was Lady in Waiting to Queen Victoria in London.

The Ivanaj Foundations of New York and Tirana that Drita founded, are lodged and occupy an entire floor in the new building complex located in the heart of Tirana e Re that includes offices and training rooms, a full size Library suitable for study and research, a Conference room with telecommunication facilities, and a large hall (Salla Ivanaj) for special events, and social activities. The overall setting of this Institute is a well-lit and technically equipped environment, with spacious areas, and comfortable climate conditions that contribute to a quiet and relaxed atmosphere for visitors and occupants alike. The land on which this complex was recently erected (and completed in 2017), belonged to Drita’s family, and included the residence that her father and uncle built when they returned from their studies in Italy and settled back in their country. The original 2-story villa of the Ivanajs was first confiscated and became the headquarter of the Italian occupying forces during WWII. Later on it was seized and used by the communist regime for a variety of purposes, such as the National Informative Service (SHIK), and as a bureau and depot at the service of the Guards of the Republic.

Drita started the proceedings of retrieving her properties in 1995, but could only set foot back into them in 2009, after indescribable hurdles of all sorts.

“When I finally entered into my property that was stripped of everything, I saw they had removed even the toilets,” says Drita in amazement.

Drita happened to be born in Italy, but from Albanian parents, and thus always had Albanian nationality. Her mother was Italian and met her future husband, Martin, while studying in Rome. Her father, however, had promised his in-laws to have their daughter return for visits, after their wedding since they had to reside in Albania. Her mother also acquired Albanian citizenship by marriage. Mirash on the other hand remained unmarried throughout his life since the woman he loved untimely passed away from natural causes at a young age.

So, they all settled in Tirana where the Ivanaj brothers built their residence. Drita recounts with a smile that Tirana had only 30 thousand residents back in the 30s, and in the area of Tirana e Re where she lived then there were only three villas.

“I was raised here, in this particular lot of land where now you see the garden of this complex,” says Drita, but, after the first 5 years, and the development of WWII, she lived in Italy with her mother for the next 12 years, where she grew up and finished her initial studies.

On Apr. 7, 1939, the Italians invaded Tirana. There was a turmoil in the city, no one knew what was happening on that day, and most left to return at later times. Her father and uncle were also involved in trying to figure out what was going on in various state offices, and at the end of that day they also left the country and ultimately reached Istanbul.

Drita and her mother never saw them again. Her father died 14 months later in an Istanbul hospital from a kidney infection, whereas her uncle returned to Albania six years later at the end of WWII. Enver Hoxha was ruling the country by then. Mirash was allowed to resume his teaching profession, while he was in the process of getting back the Ivanaj residence that, by them was housing 10 other families. He lived in one small room of it with a single bed, table and chair. Mirash was also asked to be politically involved, but he refused, and months later one night he was arrested.

While he was Minister of Public Education he had granted former dictator Hoxha a scholarship for his studies in France. But after three years Mirash cut the funds, as Hoxha was failing his exams, and spending his money on women and entertainment.

A senseless trial process was held against Mirash by the government, as versus many other persons then. Mirash was tortured for several months prior to his trial, and then he was absurdly accused and condemned for being an enemy of Albania due to alleged collaboration with Americans. He was thus convicted to prison for seven years. At sentencing time when the judge asked his reaction, Mirash replied with a question that became the quote that shaped the nature of a 40 year long dictatorship and suffering of the Albanian people: “Is there a law that has a power over one’s thought?” He was allowed a letter a month, with which he kept contact with Drita and her mother. Correspondence was of course censored, Drita says, but it was enough to just keep some sort of contact. Only 12 days prior to his release, Mirash died due to unspecified stomach and intestinal complications.

By the time Mirash died the first medical school had opened in Tirana. The bodies of the deceased prisoners were given to this faculty to conduct autopsies for anatomical studies since there were not provided with any other practical teaching methods in the laboratories. However, she recalls in gratitude that the medical students refused to touch the body of her uncle Mirash.

Although Drita lived with her father and uncle for only five years of her life, she inherited their intellect, strength, will, and dedication. Martin and Mirash were the youngest children among eight in the family. Having lost both their parents at a young age, they only had each other, when they studied abroad. They, however, constantly sustained themselves, having each other’s back. They were prolific writers, were actively involved in students’ organizations and excelled in everything they did.

When Drita left for Italy, she had only her mother, who was the one to pass along to her family history and education. She constantly reminded her that “life is the ultimate school”, and Drita learned the lessons well.

She first completed her studies in Italy receiving a Baccalaureate Degree in Science. In 1951 she and her mother emigrated to the USA, and settled in Manhattan. Drita was left alone when her mother passed away eight years later; nevertheless, through her fierceness and the many experiences she had overcome, Drita managed to outplay life in her own way, and today she runs two educational and cultural foundations with inestimable heart.

Drita received also a Baccalaureate Degree of Art in New York. She attended the IBM Systems Science Institute, and took a variety of other courses, for which she obtained specializations in Business Management, Information Systems, Computer Operations, Tactical and Strategic Planning.

Her first career was in business management. She managed the representative office of the Italian FIAT conglomerate in the USA for 15 years, way before the company started importing cars into that continent. She directed large contracts administration to provide specialized materials produced in the USA, but needed for the manufacturing of equipment in Italy that served other European countries, and even a new car factory built in Russia. For all this work she dealt with large contractors in the USA, such as General Motors, Lockheed, Boeing, Budd etc., and handled the purchases and shipments overseas of what eventually went into the production of equipment servicing the fields of aviation, naval engines, railroad cars, trucks, etc. Later on she also took care of setting up the launching of cars importing, and established car rental plans for American tourists that wanted to visit Italy. During the 15 years in this business, Drita also diversified her learning by taking evening classes in a variety of subjects, eventually zeroing in the then emerging computer industry.

In the mid 1960’s she took a course in data processing and software programming. She blithely recalls how her class included 15 people, all of whom wanted to start a better job, while she already had a good one in management, but was seeking instead a change in her career path.

“I am of those people that when I make a plan, I also have a backup one in case the first does not work out, so I am prepared for what to do next. I also take full responsibility for my actions and decisions”, Drita adds in a serious manner, and, thus, she explains how, among six different offers that became available to her at that time, she accepted a job opportunity in data processing at Columbia University, where she continued the rest of her Information Systems career until retirement.

When Drita came on board, Columbia had six large mainframes, dedicated to academia work and research, but no administrative digitized systems to manage 10,000 employees (at different level of service, from professors and lecturers to gardeners, janitors, security personnel, etc.), plus thousands of students and alumni, numerous department faculties and their administrative staff, payroll processing, and financial reporting.

Drita’s business background and her years-long experience in management gave her an advantage in achieving the objectives set for the computerization of administrative systems, and, within 6 months of her new employment at Columbia, she was promoted Project Manager and brought to successful conclusion several large applications and related computerized systems that affected several departments across the University Campus. The complexity of the things she managed and solved gave her the reputation of a problem-solver.

At Columbia she dealt with telecommunications, had access to operational hardware, interacted with academia, dealt with and supported the administration in a variety of ways. She also managed the renovation of the university’s main computer center (a 70 million dollar installation at the time), provided technical assistance and management consulting to students, colleagues and department members, and handled a data processing reorganization on campus that involved more than 120 individuals. She compiled procedural manuals for administrative staff, and in 1985 introduced computer security on campus, for which she also wrote a newsletter, and conducted specific training. “When I hear today about computer security issues, it makes me laugh,” says Drita, who thinks of herself now as a dinosaur in the field.

During her career at Columbia (over 22 years in 9 different positions) she was a member of several systems organizations and associations, for which she held office and organized meetings, trainings and courses, and annually participated in their variety of seminars, assemblies, and conferences.

Throughout her working careers, thoughts of Albania resurfaced from time to time. In 1975 she decided to visit Turkey to retrace where her father and uncle had been and where her father was buried since 1940. She sifted through old correspondence to find names and addresses, where her uncle lived and she confesses that her visit there was one of the most emotional episodes in her life. Her uncle had left two sealed packages of documents for her with some local acquaintances, not knowing whether she would able to ever fetch them.

Once she arrived in Istanbul she visited the cemetery where her father was buried, paid the overdue rent she had no knowledge had accumulated for it there, and the whole visit turned out to be a greatly moving experience. She found a beautiful headstone with two inscripted lines in Albanian for which she needed help in translation. The cemetery office staff put her in contact with an Albanian journalist, whose last name was Prodani. On the phone he asked her who she was. When he found out she was Drita Ivanaj, he insisted in meeting her that evening at 6 p.m. in the lobby of the Hilton hotel where she was staying. She recalls a mature gentleman coming in, about 20 meters away, who, after spotting her, walked toward her and said: “You are Drita Ivanaj. You are the spit image of your father!” – laughs Drita.

The journalist, however, soon became very emotional and the next day took her to the ex-consul of Albania in Turkey, who, he knew, had the packages that her uncle Mirash had left for her. From them she found out many details and some mementos, how her uncle had gone to Jerusalem to help his friend, Qemal Butka, a former mayor of Tirana, and how he had traveled to support other Albanians during his stay in Turkey. Some clues that relate to her uncle’s trial later on in Albania also surfaced from the content of these packages.

Many years later, in 1995, she was able to bring her father’s remains home in Albania and buried him beside her uncle.

The first time she returned to Albania was in 1993. The communist regime was overthrown by protesting students in 1991, the borders opened to allow free movement of domestic citizens and Albanians who had left the country years ago, and democracy was emerging. Former Prime Minister and founder (also former leader) of the Democratic Party, Sali Berisha, was serving in office as President of Albania in 1993. A number of all democracy martyrs of the country, were granted by him posthumous decorations in November 1992. At that time the government had organized such a ceremony in Shkodra and, as Drita later found out, Mirash Ivanaj was the first in that list of awards, as the father of Albania’s public school system. But Drita, the only living heir of him, was living, uninformed, in New York and thus no family member was present to accept such a reward.

Drita thankfully recalls: “In 1993 someone came looking for me in New York knowing that I existed, but nobody knew where I was. So I came to Albania in May 1993, and they redid the entire ceremony for me in Shkodra in the fall of that year. Then, I had the unexpected great pleasure and the honor of meeting some of my uncle’s ex students who were then 85 years old. I was amazed as to what they remembered from their life as students in his time.”

When Drita returned in 1993 she was amazed about how many people knew of and greatly regarded her family. She learned from them many details that she was not aware of. Former students of her uncle shared their memories with her, and during the ceremony held in Shkodra she also learned how her uncle had built the first sports field in Albania.

Over the years she was disappointed in learning how many people have used surviving documents of her family for their political purposes, and pilfered some of them from national archives. Explicit handwritten note appended by her uncle to private documents: “not to be made public unless specifically approved by my niece Drita”, were totally disregarded and abused. She had the nerve to face these situations and exposed who had no right to such mishandling and used the Ivanaj name for their own political purposes.

Meantime, a long term family friend, historian Sherif Delvina, when he found that Drita returned to Albania, conducted on his own, unsolicited research in the National Archives, and collected several hundred judgments and legal documents bearing the signature of Martin Ivanaj which he put at Drita’s disposal, soliciting her to publish them one day.

The disappointing and unacceptable experiences indicated above brought to light several issues and the fact that especially students of jurisprudence do not have much documentation from the past that they can study and use as reference in the solution of today legal cases. This means that they don’t have an archive of past similar cases and thus have no precedence they can rely upon. And this was confirmed to her by lawyers she has dealt with and students of law, who admit hardship in this achievement.

Drita stands firmly as an individual that believes in fundamental transparency of actions and justice, and situations such as the ones she was involved with and subjected to, are unacceptable and must be fought. This is one of the reasons why Drita thinks the past is so important, because one can learn from it, avoid the traps of similar mistakes, and learn how to cope with certain similar situations. ‘If there is no precedence, one cannot know something has happened before, and wheels have to be reinvented…..that is why it is so important to learn the past, in order to build the future” says Drita.

And her past is what has brought her back and she is here today. She established the Ivanaj Foundation first in New York in 1995 and the Ivanaj Foundation Institute in Tirana in 1996 for the advancement of Albanian education and culture. It took her more than a quarter of a century of persistent hard work and faith in her vision to build these institutions that carry on the legacy her family left. She admits being amazed by what she has achieved. Since she is still working and putting every bit of energy in the path she is pursuing, she doesn’t have time to contemplate about her past, and on what she did to make all this happen. “But I feel happy that at least I’ve reached these results so far,” Drita cheerfully comments.

She hopes her work will remain and continue to be expanded also after she will be gone. She says she is trying to set up whatever exists in such a way that it will perpetuate the scope and the goal that the Ivanaj brothers had worked for throughout their lives for the benefit of their country, for which she also feels strongly about, as they did.

Drita always wanted to return to Albania and establish an Ivanaj Foundation. Coincidentally, many years after she did, she found, mentioned in a document her uncle left, that he had expressed the wish that his niece would establish one day a foundation on her father’s name. She dedicated her work to both of them, for the positive impact they had on Albania in the past, but also to her life indirectly, as a message of strength and love for one’s country and people. She took early retirement to dedicate her full time to this path. The foundation in New York serves the purpose of fundraising among foreign donors and Albanian ethnics, born and raised in the US for many generations, to carry out programs and projects in Albania and surrounding neighboring countries.

She does not have children of her own, but she wants to leave this portion of contribution for the youth of Albania to use. The various trainings and workshops the Ivanaj Institute in Tirana has organized have brought so far many positive results and smiles on children, both for providing better learning practices and teaching them something new, but also for establishing stronger communities. She has perceived the kids always being ready to interact and the parents being more than grateful for their children to be able to spend time in something useful, engaging, and fun. This has proven to Drita that her investment in Albania is having a positive effect in the changes that are ongoing and will continue in one of the youngest countries in the world, thanks to its youth.

“We need fresh blood, a blood which doesn’t carry the problematics of the past, but knows the values of its past and thus should and can create a better future for itself,” she declares in hopeful tone.

Regardless of some issues that Albania is facing right now, such as the justice reform which might take a while, but will certainly give constructive future results, or the institutional bureaucracies and complexities that do need reforms to better serve the country, or the heartbreaking brain drainage that has affected the country, but could be reversed, Drita feels that Albania also has a host of other valuable assets to offer. Our country has many beautiful resources and not only natural ones. We are living in a world of transformation, which indeed provides many challenges, but, she says, life is a school and we should not be indifferent. We should be open to learning and take the lead ourselves; start working and collaborating with each other as a single entity and not as separate units.

“Democracy is freedom, but that implies self-discipline of actions, while the key to success are coordination and organization,” is Drita’s concluding statement.

Source: Tirana Times Newspaper